We have all seen bright and clear fresh oil being poured into an engine when a vehicle is serviced or when the oil is topped up between services. At the next oil change, this same oil is drained looking dirty and contaminated, much darker in colour and with a pungent odour. What we don’t see is what happens to the oil inside the engine in between the two oil services.

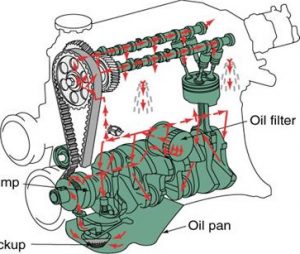

When oil is poured into an engine it settles in the oil pan, also known as the sump, at the bottom of the engine. The oil journey begins when the engine is started and the oil is drawn up through the pickup screen and tube by the oil pump. The pump then directs the oil to the oil filter to be cleaned. From the filter, the oil makes its way through the main oil gallery in the cylinder block, to the crankshaft main bearings. It then flows through oil passages (small drilled holes) in the crankshaft to lubricate the piston connecting Oil pump rod bearings. Another oil passage in the block sends oil to the top of the engine to lubricate the valve drive train, including the camshaft Pickup bearings, cam lobes, valve lifters and the valve stems. Once pumped through the engine the oil returns to the oil pan via gravity.

In some engines oil returning to the sump, drips on the rotating crankshaft and is thrown around to lubricate the pistons, rings and cylinder walls. In other designs, small holes are drilled through the piston connecting rods to spray oil on the pistons and cylinder walls.

In some engines oil returning to the sump, drips on the rotating crankshaft and is thrown around to lubricate the pistons, rings and cylinder walls. In other designs, small holes are drilled through the piston connecting rods to spray oil on the pistons and cylinder walls.

You may well wonder why the oil is dark and dirty when it is drained at the next service. Manufacturing modern engine oil is a precision operation. Painstaking effort is required to produce oils that will meet the demanding requirements of modern engine manufacturers. When new oil is poured from its sealed container into an engine, it goes from the controlled environment of the oil manufacturing plant into a completely uncontrolled chemical factory – the engine itself. Inside the engine the oil comes into contact with various harmful contaminants:

Water: For every litre of fuel burnt in the engine, about one litre of water is formed in the combustion chamber. At operating temperature this is not a problem since the water goes out the exhaust in vapour form (steam). When the engine is cold, however, some of the water goes past the piston rings into the oil sump. Water is one of the most destructive contaminants in lubricants. It attacks additives, causes rust and corrosion, induces base oil oxidation and reduces oil film strength.

Fuel: At start-up some of the atomised fuel comes into contact with the cold cylinder walls, condenses and find its way into the oil pan where it dilutes the oil. On the way down the fuel causes wash-down of the oil on the cylinder walls and accelerates ring, piston and cylinder wear. Fuel dilution also results in a premature loss of oil base number (loss of corrosion protection), deposit formation and degradation of the oil.

Soot: It is a by-product of combustion and exists in all in-service engine oils, diesel engine motor oil in particular. It reaches the engine oil by various means such as piston blow-by and the scraping action of the oil rings.

Whilst the presence of soot is normal in used engine oil, high concentrations of soot will lead to viscosity increase, sludge, engine deposits and increased wear. Soot is also the major contributor to oil darkening.

Dust: The ingestion of hard abrasive particles into an engine leads to rapid wear of engine components. These particles come in multiple forms including dust/sand, which consists of Silica. Normally the air filter will remove most of the dust from the air going into an engine. However, incorrect air filter maintenance and a leaking air intake system will introduce dust into the engine. Silica is much harder than engine components and less than 1 00 grams of dust can severely affect expected engine life.

Wear Metals: These contaminants are generated inside the engine by the wear of mechanical components. The wear debris is in the form of hard metal particles and abrasive metal oxides. Wear metal particles of sizes smaller than that controlled by standard filtration may well build up to grossly contaminate the oil. These contaminants can wear moving parts as well as clog oil flow passages and heat exchange surfaces. If wear debris accumulates in the oil, the result is more wear, generating more contaminants.

This process is known as the chain-reaction-of-wear. In addition, certain wear metals, such as copper, act as catalysts to promote oil oxidation.

To make things even worse, the oil comes into contact with high temperatures during its journey through the engine, temperatures in excess of 600 degree Celsius. The effect of elevated temperatures is oil oxidation, also called Black Death. Oxidation causes the oil to darken and break down to form varnish, sludge, sedimentation, and acids. The acids are corrosive to metals in the engine and the sludge can increase the viscosity of the oil, causing it to thicken. It can also increase wear and plug filters and oil passages resulting in oil starvation. In addition, oxidation is a major cause for additive depletion, base oil breakdown, loss in resistance to foaming, acid number increase, and corrosion. The good news is that modern, premium performance engine oils are formulated to withstand high temperatures and oxidation much better than oils from the past. It is therefore important to use a high-quality motor oil that meets the requirements specified by the engine manufacturer.

In conclusion, we need to slot in an important comment about oil change periods, which are directly dependent on lubricant life. Oils are primarily changed to get rid of all these harmful contaminants. It is also essential to fit a new oil filter with every lube service. Dirty or clogged filters allow contaminants to flow straight to your engine where they are responsible for the damages discussed above, as well as affecting fuel economy. You also risk blocking the flow of oil to your engine, which will result in engine failure. Finally, wear metals trapped in the old oil filter will promote early oxidation of the new oil.

Don’t become a victim of Black Death — change your engine oil sooner rather than later, make sure the oil conforms to the specifications recommended by the engine manufacturer and fit a new good quality filter. If in doubt, phone us on 01 1 964 1829 to ensure you are using the correct lubricants for your vehicle or equipment.

To improve (reduce) the pour point of these oils, pour point depressants (PPDs) are added. PPDs do not in any way affect the temperature at which wax crystallizes or the amount of wax that precipitates. They simply ‘coat’ the wax crystals preventing them to interlock and forming three-dimensional structures that inhibit oil flow. Good PPDs can lower the pour point by as much as 40 0 C, depending on the molecular weight of the oil.

To improve (reduce) the pour point of these oils, pour point depressants (PPDs) are added. PPDs do not in any way affect the temperature at which wax crystallizes or the amount of wax that precipitates. They simply ‘coat’ the wax crystals preventing them to interlock and forming three-dimensional structures that inhibit oil flow. Good PPDs can lower the pour point by as much as 40 0 C, depending on the molecular weight of the oil.

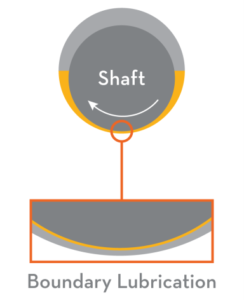

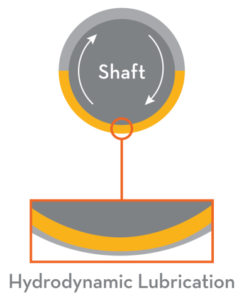

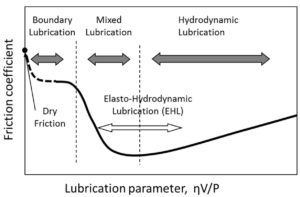

imes, we need to look at how friction and wear occur between moving machine surfaces. These surfaces appear smooth to the naked eye, but they are actually rough and uneven. Tiny peaks called asperities stick out and scrape against asperities on the opposing surface, causing friction and wear. The prime function of a lubricant is to prevent, or at least reduce, wear between surfaces moving on one another. We will endeavour to explain the lubrication of a plain journal bearing in parallel to the skiing analogy above. To enable the shaft to rotate in the bearing on the left, the diameter of the shaft must be less than the inside diameter of the bearing. This creates a wedge similar to the one between the skis and the water.

imes, we need to look at how friction and wear occur between moving machine surfaces. These surfaces appear smooth to the naked eye, but they are actually rough and uneven. Tiny peaks called asperities stick out and scrape against asperities on the opposing surface, causing friction and wear. The prime function of a lubricant is to prevent, or at least reduce, wear between surfaces moving on one another. We will endeavour to explain the lubrication of a plain journal bearing in parallel to the skiing analogy above. To enable the shaft to rotate in the bearing on the left, the diameter of the shaft must be less than the inside diameter of the bearing. This creates a wedge similar to the one between the skis and the water. he shaft and bearing asperities in a lubricated system will be in physical contact. The major portion of wear in any machine takes place in this regime. To prevent excessive wear within this regime, lubricants are formulated with additives to form a low-friction, protective layer on the wear surfaces. The base oil of the lubricant acts as a carrier to deposit the additives where they are needed. A suitable viscosity is important to ensure the oil can flow into tight spaces to lubricate the surfaces. The additive chemistry (anti-wear or extreme pressure) used within the lubricant is determined by the application.

he shaft and bearing asperities in a lubricated system will be in physical contact. The major portion of wear in any machine takes place in this regime. To prevent excessive wear within this regime, lubricants are formulated with additives to form a low-friction, protective layer on the wear surfaces. The base oil of the lubricant acts as a carrier to deposit the additives where they are needed. A suitable viscosity is important to ensure the oil can flow into tight spaces to lubricate the surfaces. The additive chemistry (anti-wear or extreme pressure) used within the lubricant is determined by the application.

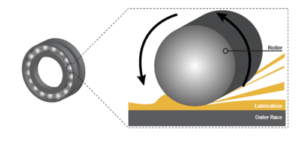

the pressure that develops is sufficient to separate the roller and raceway completely. In fact, the pressure is high enough for the surfaces to deform elastically. The deformation only occurs in the contact zone, and the metal elastically returns to its normal form as the rotation continues, hence the term elastohydrodynamic lubrication. This lubrication regime may be compared to a car tyre aquaplaning on water. It occurs when water on the road accumulates in front of the tyre faster than the weight of the car can push push it out of the way.

the pressure that develops is sufficient to separate the roller and raceway completely. In fact, the pressure is high enough for the surfaces to deform elastically. The deformation only occurs in the contact zone, and the metal elastically returns to its normal form as the rotation continues, hence the term elastohydrodynamic lubrication. This lubrication regime may be compared to a car tyre aquaplaning on water. It occurs when water on the road accumulates in front of the tyre faster than the weight of the car can push push it out of the way.

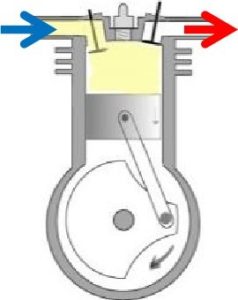

Reciprocating compressors function similarly to a car engine. A piston slides back and forth in a cylinder, which draws in and compresses the air, and then discharges it at a higher pressure. Reciprocating compressors are frequently multiple-stage systems, which means that one cylinder’s discharge will lead into the input side of the next cylinder. This allows for more compression than a single stage. Due to their relatively low cost, reciprocating compressors are probably the most commonly used compressors.

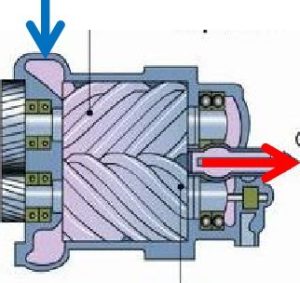

Reciprocating compressors function similarly to a car engine. A piston slides back and forth in a cylinder, which draws in and compresses the air, and then discharges it at a higher pressure. Reciprocating compressors are frequently multiple-stage systems, which means that one cylinder’s discharge will lead into the input side of the next cylinder. This allows for more compression than a single stage. Due to their relatively low cost, reciprocating compressors are probably the most commonly used compressors. These compressors use two meshing screws (also called rotors) to compress the air. In oil flooded rotary screw compressors, lubricating oil bridges the space between the rotors. This provides a hydraulic seal and transfers mechanical energy between the driving rotor and the driven rotor. Air enters at the suction side, the meshing rotors force it through the compressor, and the compressed air exits at the end of the screws.

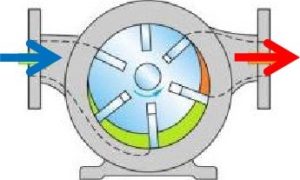

These compressors use two meshing screws (also called rotors) to compress the air. In oil flooded rotary screw compressors, lubricating oil bridges the space between the rotors. This provides a hydraulic seal and transfers mechanical energy between the driving rotor and the driven rotor. Air enters at the suction side, the meshing rotors force it through the compressor, and the compressed air exits at the end of the screws. Rotary vane compressors consist of a rotor with a number of blades (vanes) inserted in radial slots in the rotor. The rotor is mounted offset in a housing. As the rotor turns, the blades slide in and out of the slots, keeping contact with the wall of the housing. Thus, a series of increasing and decreasing volumes are created by the rotating blades to compress the air. Centrifugal forces ensure that the vanes are always in close contact with the housing to form an effective seal.

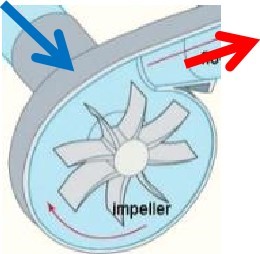

Rotary vane compressors consist of a rotor with a number of blades (vanes) inserted in radial slots in the rotor. The rotor is mounted offset in a housing. As the rotor turns, the blades slide in and out of the slots, keeping contact with the wall of the housing. Thus, a series of increasing and decreasing volumes are created by the rotating blades to compress the air. Centrifugal forces ensure that the vanes are always in close contact with the housing to form an effective seal. A rotating impeller in a shaped housing is used to force the air to the rim of the impeller, increasing the velocity of the air. A diffuser (divergent duct) section converts the velocity energy to pressure energy. Radial compressors are primarily used to compress air and gasses in stationary industrial applications.

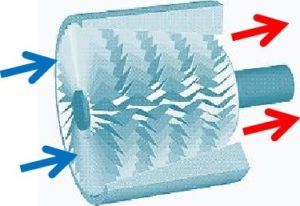

A rotating impeller in a shaped housing is used to force the air to the rim of the impeller, increasing the velocity of the air. A diffuser (divergent duct) section converts the velocity energy to pressure energy. Radial compressors are primarily used to compress air and gasses in stationary industrial applications. These compressors use fanlike airfoils (also known as blades or vanes) to compress air or gas. The airfoils are set in rows, usually as pairs, one rotating and one stationary. The rotating airfoils (rotors) accelerate the air. The stationary airfoils (stators) redirect the flow direction, preparing it for the rotor blades of the next stage. Axial compressors are normally used where very high flow rates are required. By nature of their design, axial flow compressors are almost always multi-stage.

These compressors use fanlike airfoils (also known as blades or vanes) to compress air or gas. The airfoils are set in rows, usually as pairs, one rotating and one stationary. The rotating airfoils (rotors) accelerate the air. The stationary airfoils (stators) redirect the flow direction, preparing it for the rotor blades of the next stage. Axial compressors are normally used where very high flow rates are required. By nature of their design, axial flow compressors are almost always multi-stage.