The viscosity of lubricating oil becomes progressively higher as the temperature of the oil is lowered until it becomes too thick or viscous to flow. The Pour Point of lubricating oil is the lowest temperature at which the lubricant will flow under specified laboratory conditions. It is often believed that Pour Point is the lowest ambient temperature at which oil can be used in a lubricating system, but this is a misconception.

In a system where the pump is positioned higher than the oil sump, such as an automotive engine, this will present a serious problem. We will endeavour to explain this using honey as an example. At normal room temperature honey will be above its Pour Point. When you open a jar of honey and turn it upside down, the honey will flow out under the force of gravity. Yet at the same temperature, it will be impossible to suck the honey out of the jar with a straw although the honey is still above its Pour Point. Now compare this with the engine oil circulating system on the right.

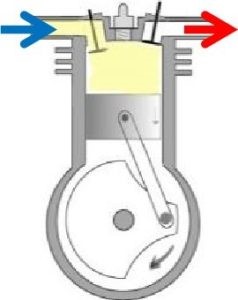

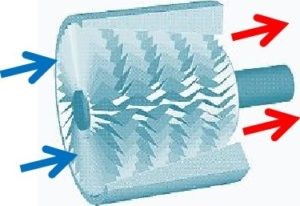

The heart of the lubrication system of an engine is the oil pump. Its function is to suck oil up from the sump (via the oil screen and oil pickup tube), and push it through the filter and into the engine to lubricate moving components. Oil pressure is created by a fluid flow restriction (orifice) in the outlet line of the pump. If for any reason, the oil pump can’t deliver its normal dose of oil, it is bad news for the engine. An oil pump failing to deliver oil to the engine is just as bad as cardiac arrest since the results are often fatal. Loss of oil pressure means loss of the protective oil film between moving engine components. With no oil to keep the surfaces apart, the engine will fail. It is therefore vital that even at very low startup temperatures, the oil must remain sufficiently fluid to enable the oil pump to suck it up and deliver it to the engine. It is crucial that adequate oil must flow from the sump through the oil screen and pickup tube to the oil pump.

When oil is cooled down, the viscosity of the oil increases exponentially with decreasing temperature. This may well result in the oil pump not being able to suck oil in from the sump, even before the Pour Point of the oil is reached. For this reason, other test methods are also used to evaluate the cold temperature behaviour of engine oil, particularly lower viscosity oils that are formulated for low temperature applications. One such procedure is the ASTM D3829 Borderline Pumping Temperature of Engine Oil – a measure of the lowest temperature at which an engine oil can be supplied to the oil pump inlet of an automotive engine. BPT is normally measured using a mini-rotary viscometer (MRV).

However, actual operational tests in Cummins diesel engines suggest that values derived by this test method may be quite misleading. First, there is a considerable difference between the actual pumpability of two oils that are identical in every way except in the nature of the viscosity index improver (VII) additive. This BPT difference may be as much as 10°C. Secondly, the values obtained using the MRV showed virtually no difference between these oils and gave values over 20°C lower than the actual BPT in the operational tests. In addition, individual engines

differ widely in the design of their oil distribution systems, which strongly affects their low-temperature performance. For example, in one system with a restriction orifice, the size of the orifice strongly influenced the time it took for the oil to reach the bearings. At -25°C this took 90 seconds with a 1.5mm orifice (and one test engine seized during the test), while it took less than 40 seconds with a 2.0mm orifice. Other influential factors are the oil screen design as well as the diameter and length of the oil pickup tube. Oil with pumping characteristics that are satisfactory in one engine may therefore not be suitable for another at very low temperatures.

With all this in mind, a good rule of thumb is that the Pour Point of the oil should be at least 10°C below the lowest anticipated ambient temperature. This will ensure dependable lubrication and better reliability in low-temperature applications.