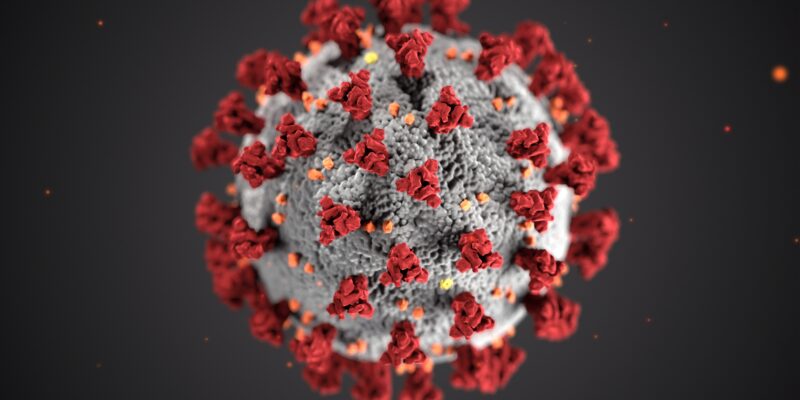

OilChat has been out of circulation for some time due to Covid-19 ramifications, but it is now back on track with this edition of the newsletter. In the last two issues of our bulletin (OilChat numbers 53 and 54) we have delved into the History of Lubrication. In this issue we will discuss how the pandemic is affecting the lubricants industry right now and the way forward.

Most lubricant users have recently experienced oil shortages and shar p price increases. But why is this and how has Covid-19 affected international lubricant supplies? We operate in a truly global economy and nothing has illustrated this more than the current, ongoing raw material shortages caused by the worldwide pandemic.

p price increases. But why is this and how has Covid-19 affected international lubricant supplies? We operate in a truly global economy and nothing has illustrated this more than the current, ongoing raw material shortages caused by the worldwide pandemic.

Base oils are the foundation of all lubricants. Lubricating base oils, both mineral and synthetics, are currently in short supply. One of the main reasons for this is that most base oils are a by-product of crude oil refining. Oil refineries distil crude oil into various streams to produce fuels such as petrol, diesel and jet fuel, other hydrocarbon products for making synthetic rubbers, paints, plastics, and lubricant base oils.

During the global lockdown travel has been greatly reduced, both commercially and personally with many of us working from home and not commuting. There are still very few planes flying hence little demand for jet fuel, which as an industry is a major consumer of fuel. The overall demand for fuel has therefore dropped dramatically and subsequently oil companies are simply producing much less fuel. Consequently base oil production has also been slashed. This shortage has led to the sharp spike in lubricant costs and supply constraints.

Lockdowns across the globe have also reduced the number of staff working at lubricant base oil facilities, leading to bottlenecks in production and increased costs. As a result orders cannot be produced and delivered in a timely fashion. The failure of a single production plant can significantly limit the global availability of certain commodities and components, especially since storage quantities are limited for budgetary reasons.

In addition to base oils all lubricant manufacturers are heavily reliant on the timely and full supply of additives and packaging. Since many feedstocks for for these commodities are by-products of the fuel manufacturing process, their production has been scaled down too. Lubricant manufacturers are therefore also experiencing a shortage of crude oil based additives and plastic containers.

These are just a few factors which have negatively impacted the oil industry and have primarily led to the shortage in raw materials and finished lubricants. Sadly, there is no way to predict or foresee what the future may hold and to determine when these shortages will be rectified.

At Blue Chip lubricants we have been proactive and have put strong contingency procedures in place to allow continued supply of our key products. We are pleased to advise that to date we have managed to supply all our customers OTIF (on time and in full) through all this chaos. Also, due to steel shortages the 208 litre drums are also in short supply but we have secured large volumes of these to ensure we have sufficient stock.

In addition we are importing container loads of heavy-duty engine oil directly from Q8Oils in Europe. We have ordered large volumes of the Q8 T750 SAE 15W40 engine oil at March pricing for delivery over the period June to August. This ensures adequate stock levels and extremely competitive pricing for all our distributors and customers. These imports have also permitted us to free up the limited local base stocks to produce other key lubricant products for our customers.

At Blue Chip Lubricants we are continuously pulling out all stops to be ahead of the crisis, but the global scenario changes every day. We deliver orders on a FIFO (first in first out) basis and it is therefore in your own interest to place your orders early to ensure you are not last in the queue.

We would also like to make use of this opportunity to thank all our loyal customers for your continued support during the pandemic and for the confidence that you have placed in us and our products. We are certainly looking forward to a long and rewarding relationship with all our staunch supporters. Together we can keep the wheels of our country turning smoothly.

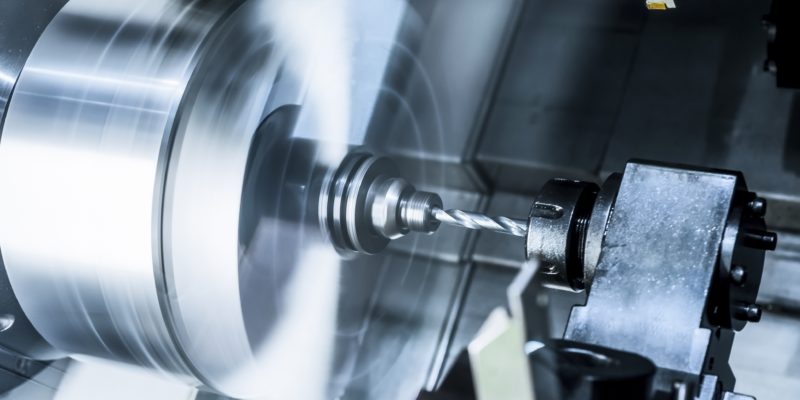

general cutting operations (e.g. lathes) the workpiece rotates whilst the cutting tool is stationary. Metal may also be removed by means of linear instead of rotational movement. In these operations, the workpiece and cutting tool move in a straight line relative to each other. The photo on the right shows such a machining operation. The cutting head (in the red rectangle) is attached to the light grey frame and can move up, down or to the left and right on slideways. The brown workpiece is fixed to a traverse table that moves backward and forward, also on slideways. The operator (with green pants) is visible on the left side of the photo. These metalworking machines can vary in size from modest basic units that produce small metal components to massive monsters designed to machine very large workpieces such as marine engines and mining machinery.

general cutting operations (e.g. lathes) the workpiece rotates whilst the cutting tool is stationary. Metal may also be removed by means of linear instead of rotational movement. In these operations, the workpiece and cutting tool move in a straight line relative to each other. The photo on the right shows such a machining operation. The cutting head (in the red rectangle) is attached to the light grey frame and can move up, down or to the left and right on slideways. The brown workpiece is fixed to a traverse table that moves backward and forward, also on slideways. The operator (with green pants) is visible on the left side of the photo. These metalworking machines can vary in size from modest basic units that produce small metal components to massive monsters designed to machine very large workpieces such as marine engines and mining machinery.